Introduction

Palm oil is extracted from fresh fruit bunches (FFB) by a mechanical process, whereby a mill commonly handles 60 to 100 mt per hour of FFB. The palm oil mill of today is based predominantly on concepts developed in the early 1950s (Mongana Report). An average size FFB weighs about 20-30 kg and contains 1500-2000 fruits (Fig. 1). The FFBs are harvested according to harvesting cycles and delivered to the mills on the same day. The quality of crude palm oil is dependent on the care taken after harvesting, particularly on the handling of the FFBs.

Figure 1. Fresh fruit bunches waiting for processing at palm oil mill.

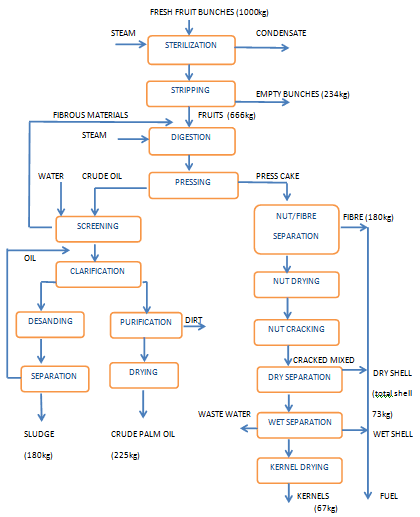

A palm oil mill produces crude palm oil and kernels as primary products and biomass as secondary product. The capacity of mills varies between 60-100 tons FFB/h. A typical mill has many operation units as shown in Figure 2. This comprises sterilization, stripping, digestion and pressing, clarification, purification, drying and storage. For the kernel line, there are steps such as nut/fibre separation, nut conditioning and cracking, cracked mixture separation, and kernel drying, storage. The dried kernels are often sold to palm kernel crushers for extraction of crude palm kernel oil. In some integrated plants, kernel crushing facilities exist side by side at the same complex.

Figure 2. Flow chart for the palm oil process (from Sivasothy, 2000).

Sterilization

This first step in the process is crucial to the final oil quality as well as the strippability of fruits. Sterilization inactivates the lipases in the fruits and prevents buildup of free fatty acids (FFA). In addition, steam sterilization of the FFBs facilitates fruits being stripped from the bunches. It also softens the fruit mesocarp for digestion and release of oil, and conditions nuts to minimize kernel breakage. Air is removed from the sterilizer by sweeping in steam in single-peak, double-peak or triple-peak cycles. In general, bunches are cooked using steam at 40 psig in horizontal cylindrical autoclaves for 60-90 minutes. The length of the sterilizer is dependent on the number of cages required for operation of the mill. Each cage can hold 2.5 to 10 tons of FFB. Steam consumption varies from 140 kg/ton FFB for a single-peak cycle to 224 kg/ton FFB for a triple-peak cycle (Sivasothy et al., 1986). Inadequate sterilization affects the subsequent milling processing stages adversely.

In recent years, new technology on sterilization saw the introduction of continuous sterilizers. Sivasothy’s (2006) continuous sterilizer showed improved fruit strippability, even with usage of low-pressure steam or atmospheric steam. The new system consists of conveyor belts taking crushed FFBs into the continuous sterilizer, where the fruits are sterilized and subsequently discharged. This reduces much of the machinery associated with conventional sterilizers. In addition, there are cost savings in terms of manpower requirements, and maintenance.

Vertical sterilizers are also available, which are much cleaner and easier to operate than conventional sterilizers.

Another type of sterilizer technology, the Tilting sterilizer (Loh, 2010) eliminates much of the machinery associated with conventional sterilizers. The technology is the latest design that offers improved milling efficiency, and reduced labour and maintenance cost.

Figure 3. A conventional sterilizer.

Stripping

Stripping or threshing involves separating the sterilized fruits from the bunch stalks. Sterilized FFBs are fed into a drum stripper and the drum is rotated, causing the fruits to be detached from the bunch. The bunch stalks are removed as they do not contain any oil. It is important to ensure that oil loss in the bunch stalk is kept to a minimum. The stalks are often disposed by incineration, giving ash as potash fertilizer, and fuel for boilers. Others are transported to the plantations for use as fertilisers in mulching near the palms. The total oil loss absorbed on the stalks depends on the sterilizing conditions and partly on the way the stripper is operated. Prolonged sterilization will increase oil loss in stalks. Irregular feeding of the stripper may also result in increase of oil loss in stalks. Stalks which have fruits still attached on them are called hard bunches, and have to be recycled back to sterilizers for further cooking. Hard bunches are detected by visible inspection.

Digestion and Pressing

After stripping, the fruits are moved into a digester where they are reheated to loosen the pericarp. The steam-heated vessels have rotating shafts to which are attached stirring arms. The fruits are rotated about, causing the loosening of the pericarps from the nuts. The digester is kept full and as the digested fruit is drawn out, freshly stripped fruits are brought in. The fruits are passed into a screw press, where the mixture of oil, water, press cake or fibre and nuts are discharged. Improvements in press designs have allowed fruits to undergo single or multiple pressing. Second stage pressing on the press cake fibres enables more oil to be extracted.

Clarification

A mixture of oil, water, and solids from the bunch fibres is delivered from the press to a clarification tank. In the conventional process, separation of the oil from the rest of the liquor is achieved by settling tanks based on gravity. The mixture containing the crude oil is diluted with hot water to reduce its viscosity. A vibrating screen helps remove some of the solids. The oil mixture is heated to 85-90°C and allowed to separate in the clarification tank. A settling time of 1-3 h is acceptable. Oil from the top is skimmed off and purified in the centrifuge prior to drying in vacuum dryer. The final crude palm oil is then cooled and stored. The lower layer from the clarification tank is sent to the centrifugal separator where the remaining oil is recovered. The oil is dried in vacuum dryers, cooled and sent to storage tanks.

Decanters

Decanters are also used in some mills as an alternative to separating the suspended solids from crude palm oil in a clarification tank. Various design of decanters are available. Their usage is, however, hampered by higher maintenance costs from the wear and tear. An advantage to the use is the reduction in palm oil mill effluent. Sulong and Tan (1996) had proposed a membrane filter press for oil and solids recovery. The cake is discharged as solid waste for fertilizer production or animal feed, while the oil is recovered.

Oil Losses during Processing

Oil losses in mills vary from mill to mill, and much attention is given to the control of oil loss. The main oil losses are from sterilizer condensate, empty bunches, fruit loss in unstrapped bunches, press cake fibre, nuts and sludge. Over-ripe bunches will lose more oil during sterilization. To minimize this, shorter sterilizer cycles are used, or better control of bunch ripeness and quality will help ensure less wastage. A typical oil loss in sterilizer is estimated to be 0.1% to FFB. Oils recovered from sterilizer condensate should be used as technical oils, as they often contain higher iron content and would reduce oil stability if mixed with the crude production oil.

Kernel Production

The press cake from the digester is fed to a vertical column (depericarper) where air is channeled to lift the fibre, thus separating the fibre from the nuts. The nuts are passed to a polishing drum at the bottom of the depericarper, where pieces of stalks are removed. A nutcracker cracks the nuts after the conditioning and drying process. A ripple mill is also used instead of nut cracker. The mixture of cracked nuts and shells is separated via a winnowing system, followed by a hydrocyclone or a clay bath. A hydrocyclone uses centrifugal force to separate the kernel from the shell using water. The clay bath principle works on the specific gravity of kernel of 1.07 and the shell of 1.17. The kernels will float while the shells sink in a clay bath mixture of SG 1.12. The kernels are then dried in hot air silos to moisture content of less than 7%. About 0.4 mt of kernels are produced with every mt metric ton of crude palm oil.

Biomass

The amount of solid palm oil waste available from a mill can be substantial. This consists of empty fruit bunches (EFB), palm kernel shell, mesocarp fibres, and possibly solids from decanters. In most cases, this biomass, especially the EFB, palm kernel shell and mesocarp fibres, is used as fuel in the mill, generating enough electricity for running the mill. Besides usage as fuel, the biomass together with fronds and trunks can be left in the fields as fertilizers. EFBs can also be combined with polyurethane ester (PU) to prepare medium density fibreboard, giving higher impact strength and better water resistance (Khairiah, 2006).

| Table 1. Dry basis calorific value of palm waste materials (Source: Yap, 2010) | ||

| Type of biomass | Average calorific value (kcal/kg) | Range (kcal/kg) |

| Empty fruit bunches | 18,795 | 18,000-19,920 |

| Fibre | 19,055 | 18,800-19,580 |

| Palm kernel shell | 18,884 | 18,880-18,895 |

| Nut | 24,481 | 24,256-24,830 |

Treatment of Raw Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME)

A palm oil mill produces an average of 0.65 tons of raw palm oil mill effluent (POME) from every ton of FFB processed. POME is the main cause of environmental pollution due to its high acidity, high biological oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD). Conventionally, anaerobic digestions in ponding systems or aerobic treatments are able to bring the BOD levels to below 100 mg L-1. Open steel tank digesters are used for tapping the biogas for power consumption. In Malaysia, certain areas have more stringent requirements (BOD of less than 20 mg L-1. Tertiary systems have been developed as new systems to provide effluent treatment in a more sustainable manner, as well as achieving the standards required by regulatory bodies. These include biological sequencing batch reactors, bio-filtration systems, systems with high aeration rates, activated sludge plants with aerobic reactors, bio-flow polishing plants, as well as membrane bioreactors. More palm oil plantations are investing into these technologies to harvest the biogas for fuel, and re-use other biomass materials for fertilizers, bio-composite materials, etc.

References

- Khairiah, B. and Khairul, A.M.A. Bio composites from oil palm resources. Journal of Oil Palm Research, April, 103-113 (2006).

- Loh, T.K. Tilting sterilizer. In: Palm Oil Engineering Bulletin, No. 94, pp. 29-42 (2010).

- MONGANA Report, Volume 1 and 2 Coopérative des Producteurs et exportateurs de l’huile de palme du Congo Belge. (1955).

- Sivasothy, K. Advances in Oil Palm Research, Vol. 1, 747, Basiron, Y., Jalani, B.S. and Chan, K.W. (eds.) , Malaysian Palm Oil Board, Kuala Lumpur (2000).

- Sivasothy, K. Continuous sterilization: the new paradigm for modernizing palm oil milling. Journal of Oil Palm Research, April, 144-152 (2006).

- Sivasothy, K., Shafil, A.F. and Lim, N.B.H. Analysis of the steam consumption during sterilization. Workshop on recent developments in palm oil milling technology and pollution control, Kuala Lumpur, p. 19, Malaysian Palm Oil Board, Kuala Lumpur) (1986).

- Sulong, M. and Tan, R.C.W. Filtration system for crude palm oil clarification and purification. In: Proceedings of the 1996 PORIM International Palm Oil Congress, Kuala Lumpur, pp. 410-424. (B. Muhamd, A.N. Ma, M.S. Affandi, Y.M. Choo, A. Kuntom, C.L. Chong, A.G.M. Top, K. Yaakob, S. Ahmad, J. Thambirajah, Z.A.A. Hassan and R. Masri (eds.), Malaysian Palm Oil Board, Kuala Lumpur) (1996).

- Yap, A.K.C. Palm waste as alternative fuel for cement plant. Palm Oil Engineering Bulletin No. 91, 13-21 (2010).

Related Resources

Lipid Library

Edible Oil Processing

In the present context, the term edible oil processing covers the range of industrial…

Lipid Library

The Highs and Lows of Cannabis Testing

October 2016 With increasing legalization of both adult recreational and medical cannabis,…

Lipid Library

The secrets of Belgian chocolate

By Laura Cassiday May 2012 Like a bonbon nestled snugly in a…