Chia: Superfood or superfad?

By Laura Cassiday

January 2017

- Chia is an increasingly popular food ingredient among consumers and manufacturers.

- The nutrient-rich seeds are good sources of α-linolenic acid (an omega-3 fatty acid), fiber, protein, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, prompting claims that chia is “superfood.”

- Few clinical trials of chia supplementation have been conducted, and those that have are limited by small samples sizes, short durations, and inconsistent results.

Chia, tiny seeds once known chiefly for their ability to sprout fuzzy green “hair” on terra cotta figurines, has now become one of the world’s hottest superfoods. Many formulators are incorporating chia seeds into a variety of foods, such as breads, granola bars, breakfast cereals, yogurt, and smoothies. Indeed, the diminutive seeds pack a mighty nutritional punch, delivering surprisingly high levels of an omega-3 fatty acid, fiber, protein, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. And as a plant, chia may represent a more sustainable source of omega-3 fatty acids than seafood. Yet are the health claims made about chia supported by solid science, or is chia simply the latest in a long list of superfoods that promise benefits but fail to deliver?

Ancient grain

Chia, or Salvia hispanica, is a flowering plant of the mint family, native to Central America. The plant produces oval-shaped seeds about 1 mm in diameter. Most chia seeds are gray with dark spots, although some are white in color (Fig. 1). Salvia hispanica, which grows best at tropical and subtropical latitudes, is now grown commercially in Mexico, Guatemala, Bolivia, Argentina, Ecuador, Nicaragua, and Australia.

FIG. 1. A. Black and white chia (Salvia hispanica) seeds. Brown-colored seeds are likely immature. B. Magnified view of chia seeds.

Chia has been grown by native peoples in Central America for centuries. The plant was an important food crop for the Aztecs in pre-Columbian times (Valdivia-López, M.Á. and A. Tecante, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/bs.afnr.2015.06.002, 2015). The Aztecs roasted and ground chia seeds for use in tortillas, tamales, and beverages. They also used the seeds for religious ceremonies and trade. During colonial times, chia consumption decreased, with the exception of a drink called “Agua de chia.” When soaked in water, chia seeds absorb about 12–14 times their weight in liquid. The seed coat contains a polysaccharide that swells in contact with water, forming a gelatinous capsule around the seed that thickens chia beverages. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers chia a food, not a food additive, making it exempt from regulation. “It appears that chia has been consumed by native cultures for long periods of time, and we are not aware of any safety concerns,” the FDA wrote in a 2005 letter to chia researcher Wayne Coates, then at the University of Arizona (http://tinyurl.com/chia-FDA). In 2009, chia seed was approved by the European Union as a “Novel Food,” allowing its incorporation into bread at up to 5%.

Chia composition

The word “chia” comes from the Nahuatl (or Aztec) word “chian,” meaning “oily.” Chia seed yields 25–40% extractable oil (Mohd Ali, N., et al., http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/171956, 2012). The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has reported that chia seed contains 42.12% total carbohydrates (including 34.4% total dietary fiber), 30.74% total lipids, 16.54% protein, 5.8% moisture, and 4.8% ash (Valdivia-López, M.Á. and A. Tecante, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/bs.afnr.2015.06.002, 2015). In addition, the seed contains high amounts (335–860 mg/100 g) of calcium, phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium, with lesser amounts (4.58–16 mg/100 g) of sodium, iron, and zinc.

The predominant lipids in chia are α-linolenic acid (ALA; an omega-3 fatty acid) and linoleic acid (LA; an omega-6 fatty acid), with lesser amounts of palmitic (saturated fatty acid), oleic (omega-9), and stearic (saturated) acids. ALA and LA are the only two essential fatty acids for humans—lipids that people must ingest in their diet because their bodies cannot synthesize them. Of the fatty acids in chia, ALA comprises about 60%, and LA about 20%. ALA is a precursor to the longer-chain omega-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic (EPA), which have been linked to various benefits, including cardiovascular and neurological health (Cassiday, L., http://tinyurl.com/fish-oil-Inform, 2016).

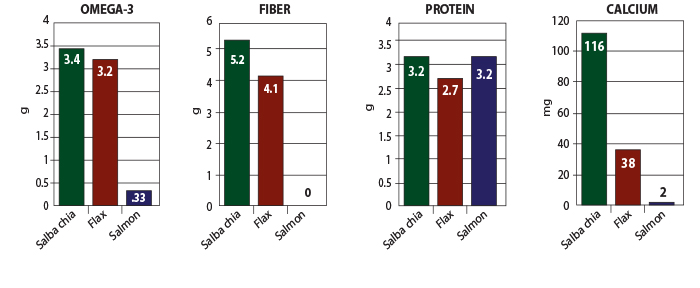

Chia contains a higher protein content than most grains and cereals (Valdivia-López, M. Á. and A. Tecante, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/bs.afnr.2015.06.002, 2015). In addition, the protein is more complete in terms of amino acid content. However, chia cannot be used as a sole source of protein because the seed lacks sufficient lysine. Chia also contains more fiber than most other grains, with soluble and insoluble fiber in a ratio of about 1:5. The antioxidants in chia, mostly polyphenolic compounds such as isoflavones, inhibit lipid peroxidation in the seeds. On a per-gram basis, chia contains more ALA, fiber, protein, and calcium than either flax seed or salmon (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2. Chia (Salba brand) has more omega-3 fatty acids, fiber, protein, and calcium than an equivalent amount of flax seed or Atlantic salmon.

The nutrient content of chia varies based on the region where it is grown and the growing conditions. Reported ranges of nutrient compositions include protein, 16–24%; total lipids, 26–34%; ALA, 57–65% of lipids; and fiber, 22–38% (Nieman, D.C., et al., http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2009.05.011, 2009; Ayerza, R. and W. Coates, Poult. Sci., 2000; Ayerza, R., http://doi.org/10.5650/jos.58.347, 2009). “The nutrient content of chia will vary depending on the area where it was grown, the elevation, how much rain if got, when it got the rain, was it very hot or cooler, and the soil conditions,” says Coates, now professor emeritus at the University of Arizona, in Tucson, Arizona, USA, and president of azCHIA in Sonoita, Arizona (www.azchia.com). “And that’s true with any crop. There’s nothing magical about chia.” According to Coates, he was one of the first researchers to study chia. In 1991, as an agricultural engineer with the University of Arizona, Coates was working on a project in northwestern Argentina. “We were working with a grower there trying to find alternative crops to beans and tobacco, the two main crops,” says Coates. “We planted a bunch of different seeds to see what would grow there, and chia did pretty well. So we started looking into what it might be good for.” Coates and his colleagues analyzed the composition of chia, helped the Argentinian growers expand to commercial production, and examined possible health benefits of the seed.

At azCHIA, Coates sells whole and milled chia, both black and white seeds. Chia is typically a mixture of 95% black and 5% white seeds. “If you pick out the white seeds and plant them, you’ll get white seeds. If you plant only black seeds, you’ll get black seeds,” says Coates. “But if you analyze the nutrient composition of black and white seeds, there’s basically no difference.” So seed color is primarily a matter of consumer preference, he says.

Chia seed maturity can also influence nutrient composition. For example, ALA increases 23% from the immature to the mature stage of the seed (Mohd Ali, N., et al., http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/171956, 2012). “The mature seeds are white or black,” says Coates. “You see pictures of chia on the web with a lot of brown seeds in it. Those are immature seeds, and they don’t have the same composition.” He also notes that many commercially available chia sources contain weed seeds and plant parts. “Everybody’s jumping on the chia bandwagon,” says Coates. “The problem is that there’s a number of people selling very poor quality chia, and the public doesn’t know good from bad.”

The question of cultivars

Through the centuries, humans have modified chia, like all crops, by selective breeding. While most commercially available chia is a mixture of different seeds, some companies offer seeds derived from a single cultivar, which they claim boosts the nutritional value and ensures consistency. Angelo Morini, founder and CEO of Anutra, LLC (www.shopanutra.com), developed the Anutra cultivar during a trip to a Mexican village called Acatic in 2002. “I found out that there are literally hundreds of different types of chia,” says Morini. “I saw the opportunity to develop, through selective breeding, a new cultivar that maximized the omega-3, antioxidants, fiber, and protein. It didn’t take us long because the people in Acatic had some real good seeds that they had been using through the years.” Morini says that unlike other chia brands, Anutra has a standard of identity as a result of its consistent nutrient profile. “You’ll get some people that will grow chia in the lowlands,” says Morini. “They can call it chia, but the omega-3’s very low, the protein’s low, the nutrition, in general, is inferior. But they can still sell it as chia.”

Another company, Salba Chia (Centennial, Colorado, USA), offers two white chia seed cultivars called Sahi Alba 911 and 912 (www.salbasmart.com). “Most chia you get at a store is grown as a wild crop, with anywhere from five to 40 different strains,” says Hank Ralston, business development manager at Salba. “With that, the nutritionals can fluctuate about 30% left or right.” According to Ralston, Salba’s South American partners analyzed 80 different strains of chia to isolate two cultivars with higher amounts of ALA and protein. “Our cultivars are not only consistent from a nutritional side, but they also have consistent absorption of liquid, so that people don’t have to reformulate finished products like breads each time they get a new batch of chia,” says Ralston. Salba chia comes in three major forms: whole, milled, or sprouted seeds.

But not everyone is convinced that certain chia cultivars are better than others. “They’re basically all the same thing,” says Coates. “There’s really only one chia, and that’s the one we started with. The bigger effect can be the climate where it’s grown.”

Fish oil substitute?

Epidemiological studies and some clinical trials have indicated a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease and inflammation with increased consumption of EPA and DHA in the form of oily fish or fish oil supplements (Cassiday, L., http://tinyurl.com/fish-oil-Inform, 2016). Concerns about the sustainability and heavy metal contamination of seafood make plant-derived omega-3’s an attractive possibility, especially for vegetarians and those who dislike or are allergic to fish. However, fish and fish oil provide EPA and DHA directly, whereas ALA in chia must be converted by the body into these longer-chained omega-3’s.

In the United States, most adult males and females already consume sufficient amounts of ALA (2.1 g/day and 1.6 g/day, respectively) to satisfy adequate intake recommendations (1.6 g/day and 1.1 g/day ALA, respectively) (Nieman, D.C., et al., http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu7053666, 2015). After absorption from the gut, ALA has three major fates: 1) β-oxidation to produce energy in many cells and tissue types; 2) incorporation into cell membranes and storage pools, primarily in adipose tissue; and 3) conversion to longer-chain omega-3 fatty acids, including EPA and DHA, mainly in the liver (Baker, E.J., et al., http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2016.07.002, 2016). β-oxidation accounts for approximately 15–35% of the ALA consumed. The conversion rate of ALA to EPA, and especially DHA, is low, with gender-related differences. Studies using radiolabeled ALA have provided estimates for conversion rates. In men, 0.3–8% and <1% of ingested ALA is converted to EPA and DHA, respectively. The conversion rates for women are significantly higher: up to 21% and 9% of ingested ALA is converted to EPA and DHA, respectively.

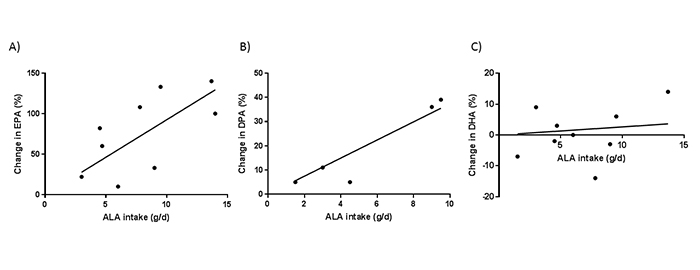

Most studies that have examined the effects of increased ALA consumption have reported higher levels of EPA in blood lipids and blood cells, whereas most report no significant increases in DHA content (Baker, E.J., et al., http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2016.07.002, 2016). There is a positive linear relationship between ALA consumption and the amount of EPA in plasma phospholipids: For each 1 g increase in ALA, there is a 10% increase in EPA content (Fig. 3). In contrast, there is little or no change in DHA levels in plasma phospholipids with increasing ALA consumption.

FIG. 3. Change in plasma phospholipid EPA (A) and DHA (B) as a result of increased ALA intake. Reprinted from Baker, E. J., et al., (2016) “Metabolism and functional effects of plant-derived omega-3 fatty acids in humans.” Prog. Lipid Res. 64: 30¬–56, with permission from Elsevier.

“Chia could be a way of increasing the EPA content of blood and cells a little bit, but it would not be as effective as eating more oily fish or taking a fish oil supplement,” says Philip Calder, professor of nutritional immunology at the University of Southampton, in the United Kingdom. “Where studies have compared ALA with EPA plus DHA for functional effects, ALA is always much weaker, on a per-gram basis. As a generalization, I would say ALA is about one-tenth as potent as EPA on a per-gram basis.”

Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids compete for the same enzymatic pathway to produce longer-chain fatty acids. For much of human evolution, the dietary ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids was about 1:1. However, modern Western diets have omega-6:omega-3 ratios ranging from 10–25:1, driving preferential elongation of omega-6s over omega-3s. Thus, the conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA might be enhanced if LA intake is decreased at the same time that ALA consumption is increased (Baker, E.J., et al., http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2016.07.002, 2016). Chia has an omega-6:omega-3 ratio of approximately 1:3.

Although ALA from chia is unlikely to provide abundant amounts of EPA and DHA, it remains possible that ALA could have its own health effects, independent from the longer-chain fatty acids. However, clinical studies of the effects of ALA-enriched diets on cardiovascular disease and inflammation have produced inconsistent results Baker, E.J., et al., http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2016.07.002, 2016).

Health or hype

Because chia’s commercial use as a food crop is relatively recent, the seeds have not been widely studied in the clinic, and existing research on chia’s health benefits is sparse and inconclusive. Animal studies have shown promise. Feeding rats chia seed improved their serum lipid profile, lowering triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol while raising high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (Ayerza, R., and W. Coates, http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000100818, 2007).

Researchers have hypothesized that the high fiber content of chia could improve satiety and thus promote weight loss. The insoluble fiber in chia has a high water-holding capacity, which could be expected to induce a sense of fullness. Nieman et al. assessed the effectiveness of chia seed in promoting weight loss and altering disease risk factors in 76 overweight or obese men and women (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2009.05.011, 2009). The study participants ingested 25 g whole chia seed or a placebo mixed in 250 mL water, twice a day, for 12 weeks. This amount of chia provided 19 g dietary fiber and 8.8 g ALA per day. Other than drinking the beverage, the subjects made no special attempts to lose weight.

After the 12-week study, the participants in the chia group had a 24.4% increase in plasma ALA levels from baseline, but no changes in plasma EPA or DHA. Also, no changes in body mass or composition of the participants were observed, suggesting that, in the absence of other lifestyle interventions, chia does not promote weight loss. The researchers likewise did not detect any changes in disease risk factors such as systolic blood pressure, serum lipoproteins, serum glucose, C-reactive protein (CRP), or inflammatory cytokines.

In another study, Nieman et al. examined the effects of chia seed oil on human running performance (http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu7053666, 2015). During prolonged, intensive exercise, ALA is strongly mobilized from adipose tissue, increasing almost six-fold in the plasma. The researchers hypothesized that ALA may serve as a fuel source during prolonged exercise, especially after carbohydrate stores are depleted. Chia, a rich source of ALA, could enhance exercise performance and reduce post-exercise inflammation. To test this hypothesis, 24 runners who had fasted overnight were instructed to drink 500 mL flavored water, with or without 7 kcal/kg chia seed oil. This dose of chia oil provided 0.43 g ALA per kg body weight, or about 31 g ALA (a large dose) for the average subject. Thirty minutes later, the participants ran on a treadmill to exhaustion.

Although plasma ALA levels were elevated 337% compared to baseline in the chia group, the run time to exhaustion did not differ between the chia and water groups. In addition, no differences were observed in the respiratory exchange ratio (a measure of fatty acid oxidation), plasma glucose, oxygen consumption, blood lactate, or ratings of perceived exertion between the two groups. Cortisone and inflammatory markers increased with exercise to a similar extent in both groups. Because anti-inflammatory effects of ALA may depend on its conversion to EPA, which takes at least one week, further research is needed to determine whether chronic ALA supplementation can reduce post-exercise inflammation.

“Chia seeds are a good nutrient source, but definitely overhyped by companies and distributors,” says David Nieman, professor and director of the Human Performance Laboratory at Appalachian State University, North Carolina Research Campus in Kannapolis, USA. “We have conducted several randomized trials, and have found no benefits on weight loss, disease risk factors, or athletic performance.”

However, some studies have indicated health benefits of chia. Vuksan et al. investigated the effects of supplementing conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes with chia (http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc07-1144, 2007). People with type 2 diabetes have an elevated risk for cardiovascular disease, and new treatments are needed to complement existing therapies. Twenty subjects with well-controlled type 2 diabetes consumed either 37 g/day Salba chia or wheat bran for 12 weeks.

Plasma levels of both ALA and EPA increased two-fold in the group consuming chia. The researchers found that the Salba chia mitigated three risk factors for cardiovascular disease: systolic blood pressure was reduced by 6.3 mmHg, high-sensitivity CRP (a marker of inflammation) decreased by 40%, and von Willebrand factor (a prothrombotic glycoprotein) was reduced by 21% in the chia group. No changes in body weight, blood lipids (triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol), fasting plasma glucose, or hemoglobin A1c were observed.

In another study, Vuksan et al. assessed whether Salba chia could reduce blood sugar spikes following meals (known as postprandial glycemia) in healthy subjects (http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2009.159, 2010). A reduction in postprandial glycemia could help explain the improvement in the three cardiovascular risk factors that the researchers had observed in their earlier study of people with type 2 diabetes. Eleven healthy individuals consumed white bread containing 0, 7, 15, or 24 g of ground Salba chia. The researchers collected blood samples and appetite ratings 2 h after consumption. Post-prandial glycemia was reduced in a dose-dependent manner. On average, each gram of Salba chia baked into white bread decreased post-prandial glycemia by 2% compared with white bread lacking chia. In addition, appetite ratings for all doses of chia were decreased 2 h after consumption, suggesting an effect on satiety.

Vuksan claims that the results from his studies on Salba chia cannot be extended to regular chia. “People make incredible profits on chia because they sell it based on our research,” he says. “Unlike regular chia, Salba has a very, very consistent composition. The composition of Salba that we analyzed in 2000 closely resembles that of Salba in our most recent study, more than 10 years later.” According to Vuksan’s experience and others’ data reported in the literature, the composition of regular chia is much more variable, he says. However, some researchers, such as Nieman, do not believe that large discrepancies in chia clinical trial results can be explained by the chia source. “All types of chia seeds are concentrated sources of ALA, soluble fiber, and minerals,” says Nieman. “There is no meaningful difference between types of chia seeds that would ‘magically’ make one seed (within the context of a normal diet) induce weight loss or alter disease risk factors.”

Formulating with chia

Whether or not clinical data currently support the superfood status of chia, consumer interest in the trendy seed is unlikely to wane any time soon. Therefore, many formulators are incorporating chia into foods, including breads and other baked goods, snack foods, and beverages.

Chia may be an attractive option for food manufacturers who want to make omega-3 claims. As of January 1, 2016, the FDA prohibited food labels from claiming that products are “high in,” “rich in,” or “excellent sources of” EPA or DHA because no reference values for the nutrients have been established (http://tinyurl.com/FDA-omega3-claims). In contrast, the FDA has taken no action against ALA claims of “high in,” “good source of,” and “more” because ALA is an essential fatty acid with a recommended intake.

From a formulator’s perspective, chia has some attractive properties compared with flax seed, another plant-based source of ALA. Because of its thinner seed coat, whole chia is easily digested by the human body, whereas flax seed must be ground to enable digestion and absorption of nutrients. However, flax seed lacks the antioxidants of chia, making it prone to lipid oxidation and reduced shelf life. In contrast, chia is very stable. According to Ralston, sensory tests have indicated that whole chia seeds are stable for 5 years from the date of harvest. “When you mill or sprout chia, or press it to produce an oil, it’s stable for about 18 months before you start to see a degradation in quality,” he says.

Several methods exist to extract oil from chia seed, including compression, solvent, and supercritical fluid extraction. The latter method typically yields the highest purity and ALA content (Mohd Ali, N., et al., http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/171956, 2012). Chia oil is not used in foods as much as whole or milled chia, primarily because oil production is an inefficient process, with over 80% waste. In addition, chia oil does not offer the fiber or protein content of whole or milled chia.

Andrew Stewart, a formulator and managing partner at Toronto-based Amazing Grains, LLC, incorporates Salba chia into all of his products. “Amazing Grains is a blend of sprouted whole grains with super seeds and fruits and vegetables,” he says. “It was the Salba chia that won us the ‘Startup Ingredient of the Year’ award presented by Nutraingredients.com in Geneva in May.” Like Vuksan, Stewart says he will only work with Salba chia because of its consistency.

“I find that the addition of Salba chia into a variety of products has the ability to lower the glycemic index,” Stewart says. He has also developed a fat-replacement system by emulsifying any edible oil, water, and Salba chia. “I’ve been able to bring down the fat content in a wide variety of products,” says Stewart.

“Some people want to include chia in their products, but they don’t really add enough to make a difference,” says Stewart. “I include Salba chia in my formulations at anywhere from 5 to 20 percent. Twenty percent goes into cereals.” When water or milk is stirred into the cereal, the Salba gels up, creating a thick porridge-like texture, he says.

The unique texture of hydrated chia can allow the partial replacement of eggs in baked goods. “To replace eggs with our Salba seed, we say to use a 4:1 ratio of either the milled product or the whole seed to water,” says Ralston. “A lot of vegans and people with other dietary restrictions are coming up with some really creative recipes using Salba.”

Although the mucilaginous texture of hydrated chia seeds works well for some applications, many consumers find the mixture, which resembles tapioca pudding, unappetizing. As a result, Morini developed a milling process that mitigates the slimy texture of chia seeds. The patented process combines mixing, milling, heating, and drying to produce extremely fine chia particles (80¬–90 microns). When mixed with water, the chai particles revert to a submicron size.

According to Morini, the microfine Anutra chia is much easier to work with than standard whole or milled chia. Because of the high content of lipids and insoluble fiber in regular chia, the ingredient can be difficult to solubilize in products like juices. “We developed a product that you can put in hot water, cold water, oils, dairy products, and it works beautifully. It stays in suspension,” says Morini. He says that he is currently working with different food companies to fortify their products with the microfine Anutra. For example, adding 1 g of the product to chocolate milk would allow a “good source of omega-3” claim, and 2 g would allow an “excellent source” claim. “They can put our product into chocolate milk, and it stays in suspension,” says Morini. “And suddenly they don’t need to use all these thickeners like carrageenan, locust bean gum, or guar gum.”

Supply and demand

Many food manufacturers who are hesitating to take the plunge into chia are worried about potential supply problems. “Their concern is, is there going to be enough production to sustain their product line?” says Coates. “With new crops, it’s always the chicken and egg thing. The producers say, “If we produce it, who’s going to buy it?’, and the big companies say, ‘If we buy it, are we going to be guaranteed a supply?’” Like all crops new to the world market, the price of chia can fluctuate widely based on supply and demand. “You can never really find out who’s producing it and how much and what’s in storage right now,” says Coates.

According to Stewart, because Salba chia is a specific cultivar produced by a single company, it is not subject to the price fluctuations of regular chia. “Right now there is a shortage of regular chia, and of course, regular chia prices bounce up and down quite a bit based on supply and demand,” he says. “One of the great things about Salba is that its price hasn’t changed in the last 10 years I’ve been working with it.”

Stewart notes that some large food companies balk at incorporating chia into their products because it is more expensive than standard ingredients such as flour, sugar, and eggs. “A lot of big manufacturers are deathly afraid to pass along the price increase for healthier products to the consumer,” he says. “But it’s been proven that people will pay more for healthier choices.” And at least for know, chia is perceived by consumers as a healthier choice than most other whole or refined grains. Whether the nutrient-dense seed lives up to the superfood hype will depend on results from larger-scale and longer-term clinical trials of chia’s suspected health benefits.

Laura Cassiday is an associate editor of Inform at AOCS. She can be contacted at laura.cassiday@aocs.org.

INFORMation

- Ayerza, R. (2009) “The seed’s protein and oil content, fatty acid composition, and growing cycle length of a single genotype of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) as affected by environmental factors.” J. Oleo Sci. 58: 347–354.

- Ayerza, R. and W. Coates (2000) “Dietary levels of chia: influence yolk cholesterol, lipid content and fatty acid composition for two strains of hens.” Poult. Sci. 79: 724–739.

- Ayerza, R. and W. Coates (2007) “Effect of dietary alpha-linolenic fatty acid derived from chia when fed as ground seed, whole seed and oil on lipid content and fatty acid composition of rat plasma.” Ann. Nutr. Metab. 51: 27–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000100818

- Baker, E.J., et al. (2016) “Metabolism and functional effects of plant-derived omega-3 fatty acids in humans.” Prog. Lipid Res. 64: 30–56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2016.07.002

- Cassiday, L. (2016) “Sink or swim: fish oil supplements and human health.” Inform 27: 6–13. http://tinyurl.com/fish-oil-Inform

- Mohd Ali, N., et al. (2012) “The promising future of chia, Salvia hispanica L.” J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012: 171956. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/171956

- Nieman, D.C., et al. (2009) “Chia seed does not promote weight loss or alter disease risk factors in overweight adults.” Nutr. Res. 29: 414–418. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2009.05.011

- Nieman, D.C., et al. (2015) “No positive influence of ingesting chia seed oil on human running performance.” Nutrients 7: 3666–3676. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu7053666

- Valdivia-López, M.Á., and A. Tecante (2015) “Chia (Salvia hispanica): a review of native Mexican seed and its nutritional and functional properties.” Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 75: 53–75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/bs.afnr.2015.06.002

- Vuksan, V., et al. (2007) “Supplementation of conventional therapy with the novel grain Salba (Salvia hispanica L.) improves major and emerging cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: results of a randomized controlled trial.” Diabetes Care 30: 2804–2810. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc07-1144

- Vuksan, V., et al. (2010) “Reduction in postprandial glucose excursion and prolongation of satiety: possible explanation of the long-term effects of whole grain Salba (Salvia hispanica L.).” Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64: 436–438. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2009.159