Poisson from a petri dish

By Rebecca Guenard

June 2021

- Making cell-based seafood is technically complicated and extremely expensive, but a select group of companies driven by a conviction that it will provide sustainability and food security for future generations are taking on the challenge

- Regulators in some parts of the world have given the cultured meats industry a green light. How will other countries regulate these products

- Projections indicate cellular agriculture could become mainstream in the next decade. What will that mean for the plant-based meat industry

- Will cell-based seafood really help ocean conservation? Some experts say cellular agriculture is not an easy solution to such a complex challenge

Our oceans are in trouble. According to a report released by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) last summer, the percentage of the world’s marine fisheries classified as overfished has increased continuously from 10% in 1975 to 34.2% in 2017. Fish consumption exceeds all other animal proteins eaten per capita worldwide and increases at an average rate of 3.1% per year. High demand results in overfishing which depletes stock faster than they replenish, lowering populations and threating future production. The report indicates that the problem is particularly acute in developing nations where unstructured governments execute limited management (https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en).

At the same time, oceans are becoming less habitable for aquatic life. They absorb anthropogenic CO2 emissions and excess heat from the climate system. Ocean temperatures continue to break record highs, threatening ecosystems and killing coral reefs around the world. Every year, an estimated 5 to 12 million metric tons of plastic enters the ocean. The waste breaks down into microplastics which get eaten by fish and, eventually, us.

With all that troubles the ocean, and given the successful development of other cell-based meats, it is no surprise that companies are interested in commercializing seafood made in bioreactors. Lou Cooperhouse, president and CEO of BlueNalu, a cell-cultured seafood company in San Diego, California, USA, started his company to address these issues.

“I realized that cell-cultured seafood could represent an amazing solution and have the most transformative potential in the entire global protein category,” Cooperhouse said.

When he started BlueNalu, he had worked in food innovation for 35 years and was inspired by the technical advances in manufacturing high-quality protein products through cellular agriculture.

Mimicking beef or chicken involves producing only one type of meat, but hundreds of thousands of different species populate the ocean. Will new food companies be able to cost-effectively produce cells differentiated into cod instead of tuna, or salmon instead of shrimp? Perhaps a more important question is whether cell-based seafood will really help with conservation efforts. Not everyone is so sure.

Cell-based seafood status and projections

Just like the technology used to culture beef and poultry, food start-ups make fish using stem cell biology and tissue engineering. A researcher extracts a biopsy-sized sample of muscle tissue from an animal and isolates pluripotent stem cells. These multifunctional stem cells proliferate in a bioreactor stew fortified with a proprietary mix of nutrients (sugars, salt, amino acids, vitamins). When the muscle cells have replicated to a large enough population, they are grafted to form skeletal muscle-like structures using techniques originally designed for medical applications.

Cell-based meats have developed quickly, but the products still have a long way to go. The technology will need significant advances for companies to eventually mass-produce filets resembling wild-caught seafood. Researchers are working on edible scaffolding to grow tissue in the striated form of muscle. Until that development is commercialized, some companies are relying on 3D printing to give their products the structure consumers expect (https://tinyurl.com/2pvzew7r). For now, most cell-based meat companies have just opted to sell products like burgers, nuggets, and cakes that work best with their current capacity to produce cell clusters (Table 1).

Cooperhouse is undeterred. In an interview with National Public Radio (NPR) two years ago, he said he plans to scale up his cell-based technology until the company can serve the needs of seafood consumers. He said he imagines a 150,000-square-foot facility in every city that meets the consumption demands of more than 10 million nearby residents (https://tinyurl.com/3bb7wyse).

Scalability is advancing slowly for these start-ups. Another cultured seafood company, Cultured Decadence, located in Wisconsin, USA, plans to make lobster meat. After a year in production, they can make about half a gram from their reactors (https://tinyurl.com/25vyz3mt).They hope to increase output enough to provide public taste tests in the next 12 months. The cost of nourishing fish cells has been reported as the biggest factor limiting expansion.

“Fish derive omega-3s and other nutritional benefits from what they eat,” says Cooperhouse. “As a result, the cell-cultured seafood we produce will have the same nutritional profile as conventional seafood.”

Providing that nutritional profile comes at a cost. The concoction of salt, sugars, vitamins, and amino acids necessary for these cells to grow introduces a production expense that these start-ups must overcome to achieve their desired scaleup. In 2019, one cell-based company produced a single salmon sushi roll for USD$200 when the market value for wild-caught salmon at the time was between USD$5–9 per kilogram.

While companies try to find ways to reduce the expense of the growing medium for cell-based fish, they are also concerned with whether they will be allowed to call their product fish. Governing agencies worldwide are in the process of deciding how to regulate cellular agriculture.

| Company name | Location | Seafood type | Progress as of July 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Art Meat | Russia | Sturgeon | Developing their technology |

| Avant Meats | Hong Kong | Fish maw (dried swim bladder) | Anticipate taste tests of their fish maw in Q3 or Q4 of 2020 |

| Blue Nalu | USA | Mahi-mahi, yellowtail | Held a tasting with multiple preparations in December 2019 of yellowtail product. Building a pilot-production facility |

| Cultured Decadence | USA | Crustaceans | Developing their technology |

| Finless Foods | USA | Bluefin tuna, carp | Held a tasting of carp croquettes in September 2018 |

| Shiok Meats | Singapore | Shrimp, lobster, crab | Produced shrimp dumpling tasting for investors April 2019 |

| Wild Type | USA | Salmon | Produced enough salmon for a group tasting in July 2019 |

Challenges with regulations

Regulations on cultured products vary by country, but typically include monitoring of production, packaging, labeling, and marketing. In Europe, cell-based products fall under the European Union Novel Food Regulation. In the United States, based on a decision announced in 2019, these products will be regulated jointly by two agencies. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will regulate cell isolation, storage, growth, and maturation. Once cells and tissue have been harvested, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) will oversee the remaining commercialization and labeling process.

Labeling is a controversial issue. Producers argue that they have the right to call their product meat, while the US Cattlemen’s Association and other groups argue that labeling such products as meat misleads the public. The US Federal Meat Inspection Act refers to meat as “any product… made wholly or in part from any meat or portion of the carcass,” which seems to justify the label. However, 12 US states have laws restricting the term “meat” on cell-based products (https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0112-z).

In late 2020, Singapore’s Food Agency was the first to approve cell-based or cultured meat for a chicken product in that country that was poised to enter the market this year. The approval was expected to be a watershed for approvals from other countries, but that remains to be seen.

Updates to current regulatory procedures will likely be necessary to keep up with advancing technologies. For example, new scaffold materials for growing filets more efficiently may be developed in the future, requiring revised oversight. And companies may eventually want to genetically modify (GM) cells, which would lead to a reevaluation of how the products are regulated. A new FDA provision categorizes a product created through the manipulation of animal DNA as a drug (https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3k48n1gr). While the Food Safety Authority has approved GM food production, contingent on thorough safety assessments, many European countries (e.g., France, Germany, Greece) have banned the production and sale of GM foods. For now, no start-ups have proposed adopting such new technologies.

Cell- versus plant-based

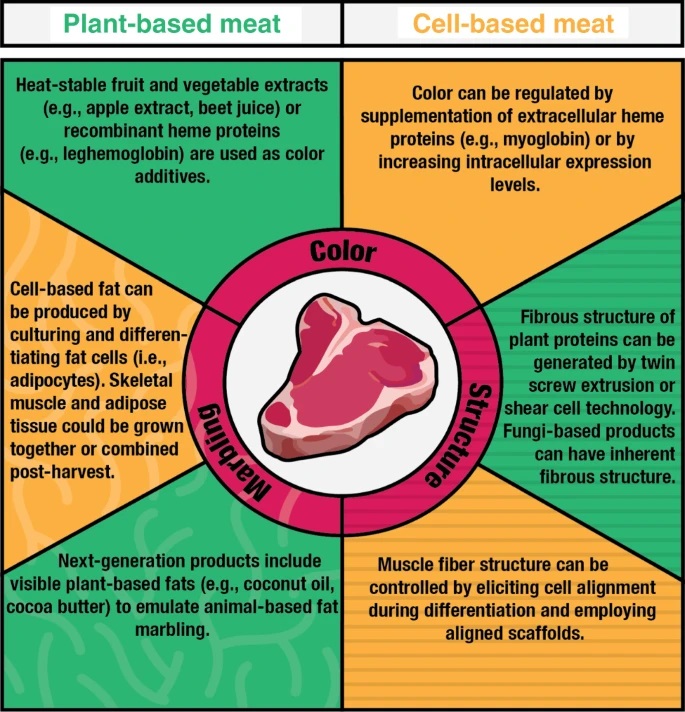

Cultured meat products will obviously compete with conventionally raised animals for consumer dollars, but they will also face-off against the existing plant-based market. Simple derivatives from soybean or wheat were developed in Asia thousands of years ago. Since then, plant-based meats have been designed to replicate the flavor, texture, and nutritional value of animal meat. In recent decades, scientists have developed several food processing technologies to improve plant protein functionalities and product formulations.

A company in Leipzig, Germany, called Bells Flavors & Fragrances has just launched a portfolio of flavor-masking compounds for plant-based dairy, meat, and fish products. A common complaint from plant-based consumers is the experience of off-notes that diverge from the conventional products these plant-based products aim to duplicate. Organoleptic compounds, (molecules that affect a product’s sensory profile) are now being addressed by several companies like Bells Flavors & Fragrances (https://tinyurl.com/3kdm96jx).

Protein sources for plant-based products are relatively inexpensive; however, the post-harvest processing and formulation advancements needed to duplicate the consumer experience of eating meat can be rather pricey. Plant-based fats, flavor enhancers, and color additives drive up the cost of these meat alternatives. Still, they are presently far more affordable than cell-based meats. Although cell-based meats have the advantage of texture and taste being identical to the real thing, the plant-based market is far ahead in terms of establishing a consumer base (Fig.1).

An April report for the Good Food Institute (GFI) states that total plant-based retail sales reached $7 billion and grew 27% over the past year—almost two times faster than total US retail food sales. This is a continuation of a growing market trend that has been observed for the past three years. More specifically, the report indicates that sales of plant-based meats crossed the billion dollar mark in 2020, reaching $1.4 billion worth by year’s end (https://tinyurl.com/4vzm92ws).

Food policy and food security experts like GFI see no reason to show a preference for one type of fish alternative over the other. They hope that consumer adoption of new cell-based products will not be price prohibitive much longer. Multiple sources result in a range of products serving unique segments of the consumer market.

Plant-based diets have evolved beyond traditional vegetarian and vegan fare as more people choose to avoid animal protein. This growth can be credited to flexitarian and younger consumer groups who are eager for a variety of environmentally responsible food options. However, some experts caution that cell-based seafood may not be the conservation miracle consumers seek.

Conservation efforts futile

Over the past half-century, the technical capacity, geographic coverage, and processing volume of fisheries have expanded enormously around the world. All fishing industry stakeholders agree that the overfishing crisis is the primary threat to ocean biodiversity (https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb6026). With millions of people consuming seafood as their protein source and the global population surging toward 10 billion by 2050, the world needs assurance that fish will be a reliable resource for our future.

Twenty years ago, Unilever and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) set up an independent not-for-profit known as the marine stewardship council (MSC) to address concerns about overfishing. Today, there are more than 400 MSC certified fisheries worldwide. The certification is meant to assure buyers, retailers, and general consumers that their wild-capture fishery conforms to internationally recognized standards for environmental sustainability. The recent FAO report on the state of the world’s fisheries indicated that in 2020, 78.7% of wild-caught seafood came from sustainably managed fisheries.

In consumer surveys, people say they take a product’s sustainability into account when making a purchase (https://tinyurl.com/k8kusw9s). This behavior has increased by 10% during the pandemic, with consumers saying they are now more conscious of the environment. One of the sustainable shifts many consumers are making is in their dietary choices, eating vegan, for example, to circumvent practices they perceive to be cruel to animals or unsustainable.Researchers at the University of Santa Barbara, California, question whether such choices can really have an impact on a conservation problem like overfishing.

The new surface cleaners described here are examples of the industry’s ingenuity in certain sectors. But the industry must still solve the challenge of surfactants if it wants to reach its environmental goals. In a recent interview, Neil Parry, R&D program director for biotechnology and biosourcing at Unilever in the United Kingdom, said that in terms of volume, surfactants continue to be the biggest obstacle to sustainability. His company recently announced that in the next 10 years they will go from 16% renewable or recycled carbon to 100% (https://cen.acs.org/business/consumer-products/Cutting-carbon-cleaning-Unilever/99/i2).

In a recent journal article, the team argues that the best path to achieving ocean conservation is not through the development of a cell-based seafood alternative (https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12541). To achieve such a goal, the product must first make it onto the market, a feat in and of itself. Cell-based seafood would then need to become so desirable that demand for wild-caught seafood decreases and fish stocks rebound.

The paper’s authors argue that for this outcome to prevail, fishers would need to find other careers, and the cultural acceptance of bioreactor-produced fish would have to dramatically increase—assuming that this technology can be developed on a large scale at a lower price than wild-caught fish which, as previously mentioned, is currently not the case.

Until the costs come down, cell-based seafood will have a difficult time breaking into the market. And even then, research results indicate plant-based products could be more popular. Surveys gathered from consumers who received information on the sustainability of conventional, plant-based, and cell-based meat led researchers to predict respective market shares of 72%, 23%, and 5% for each (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101931). A market forecast by the US management consulting firm Kearney had a more positive outlook for cell-based meat and predicted that in the next 20 years the market share would be split about evenly between the three (https://tinyurl.com/avxzszr2).

If conservation does not win consumers over, cell-based seafood can certainly claim to be clean. Cells grown in a bioreactor are not exposed to the mercury or microplastics pollution from the ocean. Consequently, the fish products they form will be guaranteed toxin-free. That could be enough of an incentive for fish eaters to convert from conventional products.

Cooperhouse says he is not looking to replace wild-caught or farm-raised seafood but is aiming to become a third alternative for vegan and vegetarian seafood eaters (https://tinyurl.com/3bb7wyse). “Consumers are changing. They are looking at health. They are focused on the planet,” Cooperhouse said to NPR. “This is not a fad or a trend — this is happening.”

Companies focused on plant-based products as meat alternatives will want to keep an eye on the growth of the cultured meat industry. If forecasts are correct, they can expect competition from this sector in the coming decade.

About the Author

Rebecca Guenard is the associate editor of Inform at AOCS. She can be contacted at rebecca.guenard@aocs.org

Information

Overfishing and habitat loss drives range contraction of iconic marine fishes to near extinction, Yan, H.F., et al., Sci. Adv., 7(7): eabb6026, 2021.

The long and narrow path for novel cell‐based seafood to reduce fishing pressure for marine ecosystem recovery, Halpern, B.S., et al., Fish Fish., 00: 1–13, 2021.

Consumer preferences for farm-raised meat, lab-grown meat, and plant-based meat alternatives: Does information or brand matter?, Van Loo, E.J., Food Policy 95: 101931, 2020.

Plant-based and cell-based approaches to meat production, Rubio, N.R., N. Xiang, and D.L. Kaplan, Nat. Commun. 11: 6276, 2020.